The result of the U.S. presidential election is clear: “Polls are dead,” said many pundits following the 3 November election where, instead of a predicted landslide, record-breaking voter turnout produced razor-thin margins.

When polling and historical benchmarks fail to predict the future, what works? Frequent scenario planning is one answer. Scenarios, of course, need to be updated when events are rapidly changing. Scenarios inform the work of both Democrats and Republicans in the U.S. elections. This year, Democrats’ scenario plans included dampened turnout due to the pandemic and other bubbling issues. In response, they waged an intense effort to dramatically increase early in-person and mail-in voting.

Republicans and the incumbent president saw declining poll numbers but were buoyed by turnout and the fervor of those attending campaign rallies. Their scenario planning produced a decision to continue large-scale rallies in spite of COVID-19 warnings, deciding that the benefits outweighed the risks of community spread. They narrowly lost the bid for a second-term president but made unexpected gains in the legislature and energized their base.

How Can Communicators Use Scenario Planning?

Scenario planning works for everything from scheduling a product launch to choosing partners for new initiatives and many other endeavors. It’s especially valuable in crisis communication planning and response.

Crisis planning and response is a series of risk assessments, and scenario planning is one of the best tools to assess risks against potential benefits. In working with organizations in crisis planning, I ask a cross-functional internal team of managers to be as specific as possible in listing all the possible risk scenarios that could require a public response: those that have happened, new potential threats and even events that seem highly unlikely.

Once we categorize the various scenario events, we ask a hard question of each one: Is this really a crisis that needs an external response? Sometimes an isolated event demands immediate attention, even CEO engagement, and potentially causes a bit of chaos and dropped balls to attend to the crisis. Anyone who shares responsibility for both internal and external communication can speak to internal issues that do not rise to the level of a public response. Then, there are many other “alerts” that live and disappear within 24-48 hours and don’t deserve the full court press and high-level response they sometimes get.

I once received a crisis alert call from an attorney and his client who owned a chain of restaurants and wanted immediate help in a public response. After hearing the details, I realized that the owner was personally offended that his restaurants had been criticized by a competitor on a Facebook page and wanted action. Some quick research showed this was an isolated social post that received little engagement and would only be exaggerated with a public comment. I explained the scenario for escalation that would undoubtedly occur with any comment. The action I counseled was “no action.” We continued to monitor social sites, and it quickly died out.

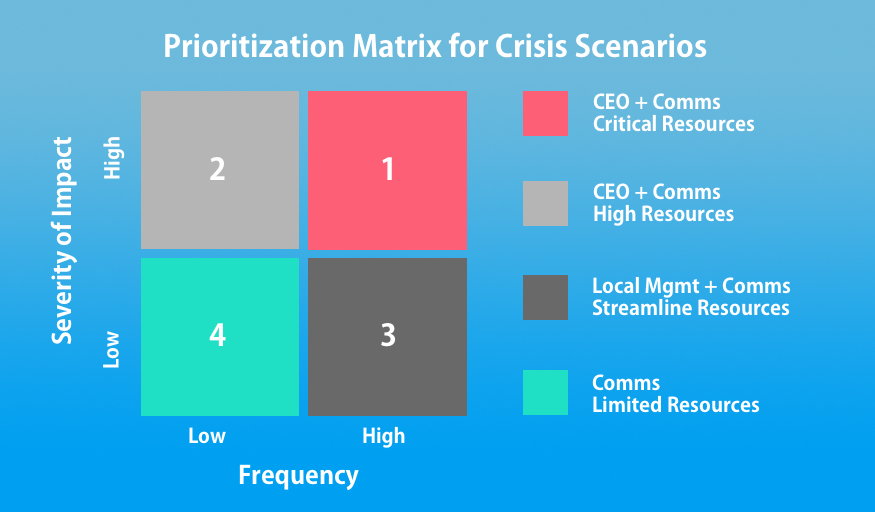

Scenario planning can clarify priorities, especially when it comes to crisis planning and the allocation of communication resources. Consider these four factors to determine priorities:

- Likelihood or frequency

- Scope and potential impact

- Short-term versus ongoing issue

- Risk of reputation impact

Next, organize your possible scenario events by impact level, scope and frequency. Prioritize resources for high-impact, wide-scope events. If these high-impact events are happening with some frequency in your industry (e.g., a food safety issue), this should be a high priority even if it hasn’t yet happened at your company. The second priority is low-likelihood events that have the potential for the greatest negative impact.

A frequent, high-impact scenario might be a data breach at a consumer products retailer. A less frequent breach would be a data leak by a health care provider or health insurance firm, putting patient confidential records at risk.

The third and fourth levels of priority are scenarios that may be narrow in scope but occur with regularity. A severe weather event impacting operations in a specific location may be frequent due to the location’s proximity to seasonally strong hurricanes, typhoons or wildfires. It’s essential to have a streamlined, off-site response that can be triggered at a moment’s notice. Know in advance what resources the company can commit to help in a crisis. Don’t wait for perfection when immediacy is needed. Few will forget your absence in the critical early hours while you are waiting to get it just right.

The Method x Hitachi Trust 2030 Project

I’ve long viewed crisis work as relatively short term in nature, so I was fascinated to read about the Trust 2030 project produced by the design firm, Method, and their client, Hitachi.

Hitachi, a global engineering firm that builds major infrastructure projects like power plants and transportation systems, wanted to know how changes in society might impact trust and behavior in the future. The answers could influence the design of the multi-year construction projects to ensure they anticipated societal changes that would affect their usability and success.

Method’s U.K. office and Hitachi’s Tokyo innovation team engaged in a three-month design project to envision three possible scenarios in response to a fictional pivotal event. They chose a major data breach that exposed gross human rights violations by a government official.

I talked with Joshua Leigh, associate director at Method and lead on the project, for my podcast, Trusted Sources to learn more about this. He shared that after extensive research and analysis, Method employed predictive design thinking and used physical day-to-day objects to convey how life would change in three scenarios:

- Decentralized and transparent

- Centralized and curated

- Distributed and autonomous

In the first scenario, citizens in a completely transparent society carry connected ID cards with contextual information about their past performance, skills and current state of mind. It enables trust where it wouldn’t otherwise exist. In scenario 2, a data capture device gives all of our personal data to one company that provides and curates personalized goods and services. Finally, scenario 3 occurs when the breakdown in trust is so complete that individuals forego convenience for personal well-being and safety. Mistrust in global pharmaceutical firms, for example, could result in hyper-local production of medicines where users can oversee what they’re getting and accept a small supply at a time, perhaps only a week’s worth of pills.

Leigh believes advance scenario planning might have changed the rollout of some new technologies that have become central to our lives in only a few years. He points to the idealistic Silicon Valley pioneers, eager to create a better world, who created technologies that would change it in ways they couldn’t imagine. Unlike traditional firms that earned trust over time, companies like Google, Facebook and various social platforms are less than 15 years old, but most of them gained almost instant trust with widespread free use. “We give almost all of our private data to these companies in exchange for their use,” Leigh says. “And now, we’re starting to see some of the consequences.”

Joanne Henry, SCMPJoanne Henry, SCMP, is president at PR for Good, providing communications counsel, media relations, advocacy and social impact work. Her podcast, Trusted Sources is about trust and reputation and is available on most podcast platforms. She has a 30-year track record of success in crisis communications, public relations, crisis, branding and advocacy work for start-ups through Fortune 500 companies. She is a founder of three agencies and the Common Good Breakfast series, now in its 12th year. Her early career included investor relations and financial research; she also is considered a leading expert in food safety crisis communications. Joanne is a long-time IABC member and has been active as a chapter leader, chapter advocate for the Pacific Plains Region and a Gold Quill judge. She currently chairs the IABC Trends Watch Task Force. Joanne holds a B.A. in English and journalism from the University of St. Thomas and has studied economics and finance at the University of Minnesota. She lives with her family in Minneapolis.