2020 has been a year of reinventing, from conferences, to how we work, how kids go to school and how we celebrate holidays. It’s also been a time to rethink how we show our value to senior leadership.

For years, we’ve been asked to show our ROI for communications. And for just as many years, I’ve had to explain to chief marketing officers (CMOs), chief communication officers (CCOs) and the occasional chief financial officer (CFO) why we can’t.

First, let’s agree on what ROI is not. It is not “return on influence,” “return on impressions” or any other similar nonsense. Using any of these alternative definitions will earn you enduring scorn from your CFO and everyone who works for them.

ROI is an abbreviation for the business term “return on investment,” created by DuPont in the 1920s as a financial measure. It is calculated by subtracting the cost of an investment from the gain of an investment and dividing that by the cost of the investment, expressed as a percentage. The equation looks like this:

ROI = (R – I)/(I)

Where R = return and I = investment.

To calculate ROI, you must take into account not only the revenue that was generated from your efforts, but all the costs involved in generating that profit. I have yet to meet anyone who regularly calculates the investment in a communications effort AND the actual profit (not revenue). This is why we need to reinvent how we talk about communications value.

First, we need to accept that organizational value comes in many forms, from greater efficiency to reduced costs. So, let’s walk through some basic steps to reinventing how you measure your value, without getting laughed out of the board room by the CFO.

Step 1. Get consensus on what your business value is supposed to be.

The first step is to get agreement on what communications value and success mean to your organization. Start with your strategic priorities or annual plan. Then have a conversation with senior leadership to get consensus on how it perceives communications contributions to the successful implementation of those goals. Unless consensus is reached on what leadership expects as a return, you have no framework with which to even begin the process.

We know this can be challenging. Many a CEO thinks that “success” is a front-page profile of them in the Wall Street Journal. You need to push back hard on that notion, and question how that actually brings revenue into your organization. Chances are it can’t. What communications value means to most companies is:

- Protecting the brand

- Increasing brand value

- Increase brand loyalty

- Lower recruitment costs

- Increase the talent pool

- Increase the stock price

- Lower legal costs

Chances are good that at least a couple of those benefits will support your corporate strategy, just make sure that leadership agrees on which ones.

Step 2. Define acceptable proxies.

Next, gather your team to brainstorm about how they believe your activities contribute to those corporate goals and priorities. Define the path from what your team does every day to those corporate goals.

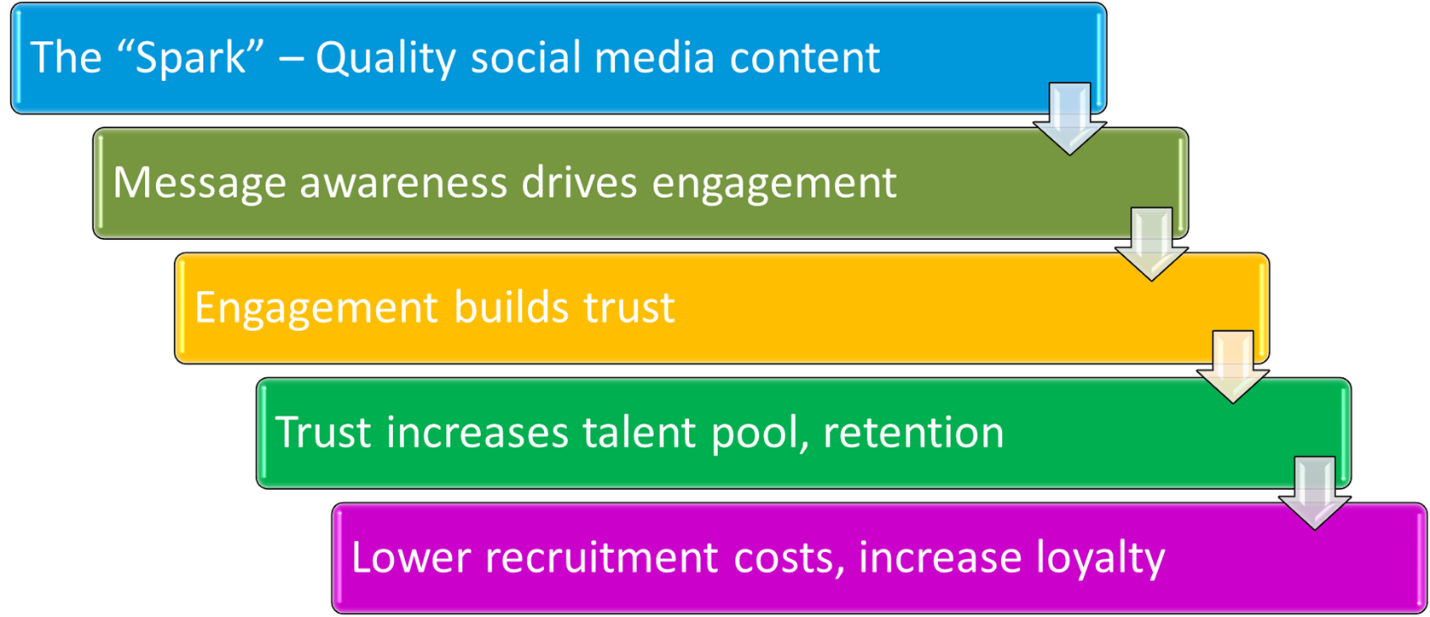

A typical path might start with someone creating a piece of content that contains the appropriate persuasion message. It is then posted somewhere and, presumably, your target audience interacts with it. This path to purchase might look like this:

If your goal is sales-related — i.e., generate leads — make sure you get input from marketing and sales to ensure they agree with the elements and order of your path. If you have a consumer research or market research department, get input from them as well.

From those discussions, develop a list of proposed metrics. These are what we call “acceptable proxies.” For example, if one of your goals is to build trust and credibility, imagine actions that imply credibility — i.e., sharing content, recommending an event, downloading a white paper — all things that people don’t do if they find your content untrustworthy or incredible.

If the goal is to develop leads, look at historical data in your web analytics to see what path people take before they actually request more information or a sales call.

Make sure you define acceptable proxies that are specific to your department. Ideally, every piece of content would be tagged with PR, social media or some other indicator of which department originated the content.

Step 3. Determine a benchmark.

The most frequent complaint from senior leadership when reviewing a communications report is, “What does it all mean?” The problem is that unless results are put into context, they are meaningless. You need to establish what your results will be compared to.

In its collective mind, does senior leadership see “success” as beating the competition? Improving results over last year or quarter? Producing more results than paid advertising, direct sales or some other operational effort? Without clarity on what you are benchmarking against, you can’t put your number and metrics into context.

Step 4. Bake some cookies.

Today, having the necessary data to do the calculation is critical to measuring results. Cookies unlock all kinds of doors and drawers and data files, whether they’re in accounting, finance, sales or market research. Typically, communication need at least two, if not three, types of data to show results.

- What people are seeing, i.e., some sort of media content analysis to determine what people are reading, seeing or watching about you and, ideally, your competition.

- How people are feeling: What do people think about your brand or industry? Typically, this data comes from market research, but it can be supplemented with social listening data to see how people are talking about you online.

- What people are doing: How are they interacting with your content on the web or social media? This data can come from web analytics, social analytics or your CRM system.

Cookies are the easiest way to get to data that is typically locked away in another department. (Hint, if cookies don’t work, try a nice Cabernet, or maybe a single malt.) When all else fails, resort to coercion. Deliver a report with blanks for the missing data and tell leadership that you can’t actually show your results because Andrew from accounting wouldn’t give you the data you needed.

Step 5. Analyze your data until it tells a story.

Next, go back to your goals and your proxies and pull out the metrics that relate to those goals. Ignore all the rest of the data that you will no doubt accumulate.

Remember that no matter how good you are, not every program, initiative or campaign will generate equal value. Some will perform better than others, some may not perform at all. Some may perform beautifully but will have cost a fortune or burnt out your staff.

Take your data and make sure all the time frames are the same. Ideally, you can analyze results week-to-week to pinpoint what was going on in your company or department at that particular time. If you can, run correlations between your data points to determine whether, for example, positive media had an impact on web downloads, or whether particular events generated greater social engagement than others.

Then, rank all campaigns from worst to best based on their contribution to your goals. (Looking at the worst first helps identify where you need to focus your recommendations for improvement.) Then, put a resource value next to each one (take into account staff time and morale as well as money.) It doesn’t have to be precise, just a ranking from “easy peasy” (1) to “worst nightmare” (10).

Gather your team and discuss those results. Why did some deliver more value than others? What contributed to any failures? What will you do differently next time? The answers will form the basis of your report.

Step 6. Create a report that will make your board swoon.

Boards don’t want good news — they want to know what they need to worry about, how results were generated and how you’re going to improve next time.

Analyze your data to find the answers to those questions. Once you’ve got the answers, use your data to illustrate your conclusions. Charts and graphs are great persuasion tools in a board room, but only if there’s a narrative that tells people what they need to do or think about the data.

Remember, everyone on your leadership team essentially wants the same things you do — a more successful, more efficient organization. It’s just that they don’t always speak the same language as you do. Some may only speak in numbers and graphs, but your analysis will tell them the story they need to learn from those numbers.

Katie Delahaye PaineKatie Delahaye Paine, measurementqueen@gmail.com, (@queenofmetrics), has been a pioneer in the field of measurement for more than three decades. She founded two measurement companies, KDPaine & Partners Inc. (now Carma) and The Delahaye Group (now Cision.) Her latest company, Paine Publishing, helps organizations define, design, and implement measurement dashboards. Its newsletter, The Measurement Advisor, is the industry’s most comprehensive source for best practices in communications measurement.

She was recently awarded the prestigious IPR Jack Felton Medal for Lifetime Achievement, an award given for lifetime contributions in the advancement of research, measurement and evaluation in public relations and corporate communication. Paine is a Senior Fellow of the Marketing & Communications Center at The Conference Board and a founder and member of the Institute for Public Relations Measurement Commission

Her books, “Measure What Matters” (Wiley, March 2011) and “Measuring Public Relationships” (KDPaine & Partners, 2007) are considered must-reads for anyone tasked with measuring public relations and social media. Her latest book, written with Beth Kanter, “Measuring the Networked Nonprofit: Using Data to Change the World,” is the 2013 winner of the Terry McAdam Book Award.